Thirty minutes before a midnight screening of Tommy Wiseau’s Big Shark at Chicago’s Music Box Theater, the man sitting in front of me and my husband turned around with a sly grin and asked us “Are you cowboys?” I immediately guessed where this was going, so I played along and told him, straight-faced, that no, we were not cowboys. “OK, then. You might request these,” he said, offering me a box of tissues.

I had no thought what he was referencing, but I got the vibe immediately. It was the equivalent of a Rocky Horror image Show veteran asking a newbie “Are you a virgin?” Clearly, this man was in the know about a Big Shark gag I wasn’t in on yet. But just as clearly, he had a plan involving any series in the movie, and he wanted us to be ready to participate.

Of course we were in. I grabbed a tissue and braced myself for impact. Big Shark is clearly Wiseau’s riff on “huge predator menaces tiny town” movies like Jaws or The Meg, though tonally, it’s closer to Syfy originals like Sharktopus. But I wasn’t truly there for the shark attacks. I’d showed up to see whether Big Shark was already turning into the fresh edition of Wiseau’s infamous movie The Room. This invitation to participate in any unknown gag made it clear that I was about to get precisely the experience I’d been hoping for.

Oh hai, shark

Tommy Wiseau’s first movie, The Room, is 1 of the most baffling pieces of outsider art always made, and its success communicative is equally baffling. The communicative is incoherent. The script is full of non sequiturs. Characters and game points are introduced, then vanish forever without comment. An excruciating sex scene is shown twice. The cast offers up any of the most awkward line readings and physical blocking known to mankind.

Wiseau stars in the film, and his half-mumbled, half-shouted performance and periodically mangled English are so mesmerizingly weird that many of his line readings — “Oh hai, Mark!” “You’re tearing me apart, Lisa!” “Everybody betray me! I fed up with this world!” — have become memes, merch, and instant shibboleths, traded around to identify those who have experienced The Room in all its confusing glory.

Theatrical showings of The Room rapidly became focused on audience participation and engagement. An full Rocky Horror-esque ritual has grown up around the movie. Participants throw plastic spoons, recite along with any lines and respond to others, and run down to the screen to imitate the movie’s phenomenally clumsy football-tossing scene or to interact with Wiseau’s on-screen character. The regular is part mockery, part celebration, part ego-driven public performance, as participants compete to come up with the cleverest fresh quip or get the biggest laugh.

Big Shark is not much better as a movie. More than a decade after The Room premiered, it seems impossible that Wiseau hasn’t gained any measurement of self-awareness about his filmmaking. He’s been in on the gag for years, attending screenings of The Room, selling his own “Oh hai Mark” merch, and even appearing in The Disaster Artist, the 2017 movie adaptation of Greg Sestero’s tell-all book about how The Room went so wrong. It was always a toss-up, though, whether his movie’s rep as 1 of the worst films always made would push him to improve as a filmmaker, or whether he might consciously effort to grow his story by purposefully creating another infamously bad cult movie.

Big Shark shows no sign that he did either of these things.

You’re tearing me apart, shark

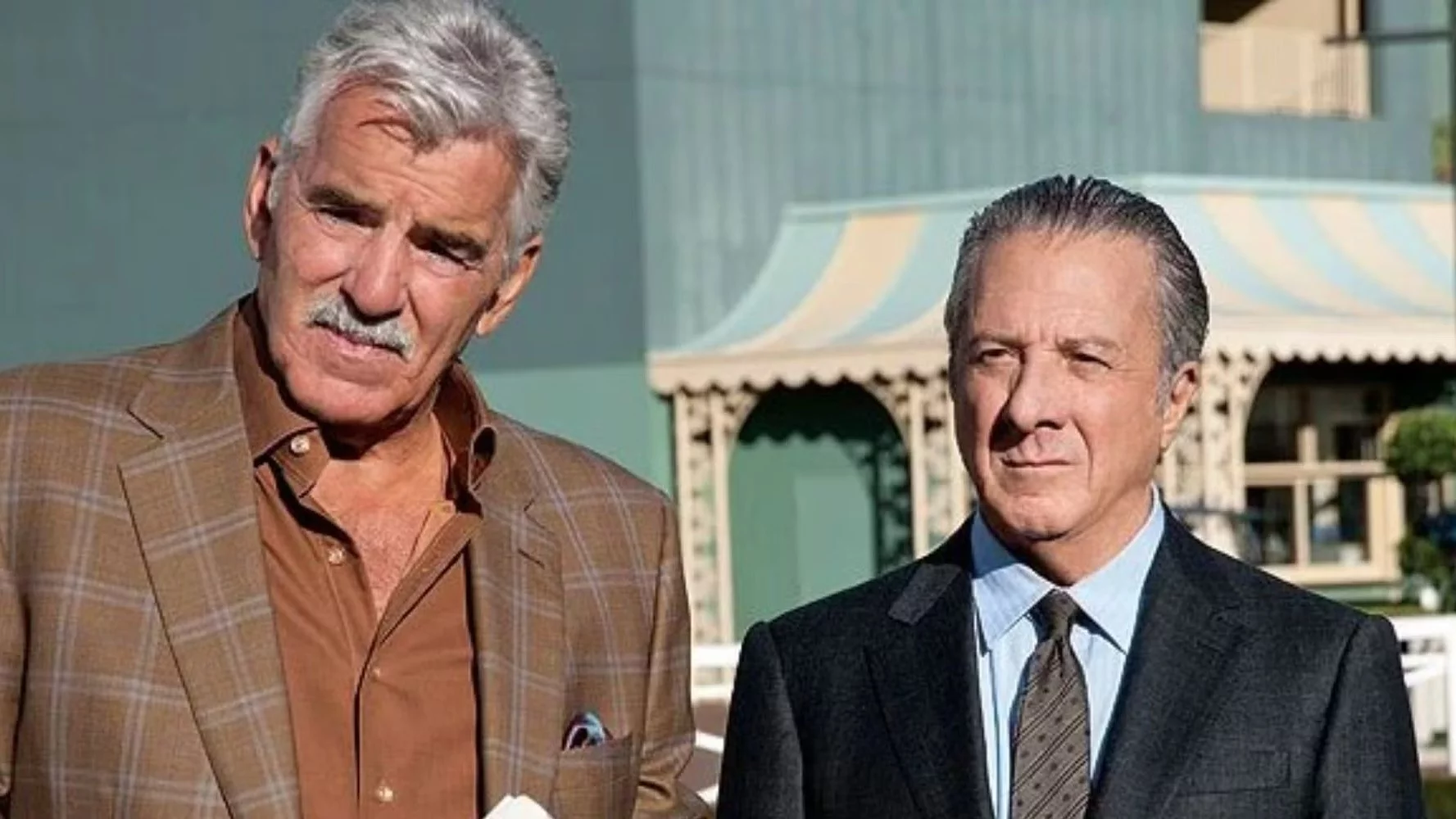

Image: Wiseau-Films/YouTube

Big Shark centers on 3 volunteer firemen — game and rugged Tim (Isaiah LaBorde), seemingly half-stoned Patrick (Wiseau), and angsty Georgie (Mark Valeriano) — trying to halt a giant shark from terrorizing fresh Orleans. (Sestero, Wiseau’s The area co-star, was originally cast as Georgie and appeared in an early teaser trailer, but dropped out of the task before production.) The shark, which the characters inform us countless times is simply a 35-footer, skates through the streets weightlessly on abrupt inexplicable gushes of shallow water, snatching people up in its jaws like the improbable digital monster that leaps out of nowhere to gobble up Samuel L. Jackson mid-speech in Deep Blue Sea.

Why does it fall on 3 firemen to save the city? Why is no 1 else doing anything about the shark? Why do the firefighters frequently interrupt their shark-hunting plans for beer pong and clumsy fights with their girlfriends? Why do they keep repeating things they’ve already said, and holding atonal impromptu sing-alongs? This is the mystery of a Tommy Wiseau movie.

But there’s no sign that any of it is calculated or cunning. Big Shark is as mawkishly sincere as The Room, complete with likewise unmotivated relation drama, played out in likewise unconvincing ways. erstwhile again, the editing is an absolute conundrum, with redundant scenes and reused footage. The sound mix is terrible, with characters’ voices blaring 1 minute and all but disappearing the next, even within a single scene. A daytime series will abruptly become a night sequence, and vice versa, with no sense of elapsed time. Much of the dialog appears to have been improvised on the day of shooting, with only broad guidelines about the intent of any peculiar scene.

Wiseau hasn’t gotten any better at laughing, crying, or talking in ways that believably mimic any kind of previously known human behavior. The pacing is simply a snooze, the shot-to-shot continuity is nonexistent, and the titular large shark is simply a ridiculously cheap, Birdemic-level peculiar effect that computer-savvy adolescents are routinely outdoing for amateur movie projects on YouTube.

The audience loved it.

Ha ha ha, what a story, shark!

Image: Wiseau-Films/YouTube

Early on in Big Shark, it became apparent that the guy in front of us wasn’t the only 1 who had already seen the movie. Big Shark currently isn’t available for streaming or online rental; it can only be seen in theaters, as part of an extended nationwide tour ahead of a promised digital release. (Finding out about screenings in advance is simply a small challenging: Wiseau’s website and his

social media outlets are only erratically updated, though The Room’s website seems to have the most fresh info.) You might think that limited availability would slow down the growth of a fresh Big Shark-based theatrical ritual. But many of the people at my screening were clearly veterans of The Room, and they came prepared.

Tim and Patrick go diving respective times in the movie, seeking the shark and encountering the same batch of plastic kelp. all time it reappeared, an audience associate led a sing-along to the tune of The Beatles’ “Help!”: “Kelp! I request somebody! Kelp! Not just anybody! Kelp! You know I request someone! Keelllllp!” erstwhile Patrick’s girlfriend, Sophia (Ashton Leigh), tells Tim’s girlfriend, Charlotte (Erica Mary Gillheeney), to “implement discipline” with him to avoid relation problems, individual in the audience made whip-cracking noises. The constant mentions of the “big shark” were met with a collective, choral “How large was it?” and an equally choral consequence of “Thirty-five feet!” A glimpse of a transparent egg with an embryonic shark inside naturally started a sing-along of “Baby Shark.” all on-screen devouring earned a cheer of “Big shaaark!”

The continuity problems got plenty of callouts. Wiseau’s character wears oddly bright-hued gloves that change colour from shot to shot: individual behind me yelled “I hatred my old gloves!” with a Wiseau accent to mark all colour change. “Why is it night?” all time a daytime scene goes dark was a popular question. Tim seldom appears to be driving the same vehicle from scene to scene, which got a repeated catcall of “Let’s change cars!” Patrick repeatedly yowls Sophia’s name during a peculiarly weird scene where she tries to boot him from their home for unclear reasons: 1 wag in the back of the theatre went full Streetcar Named Desire, echoing all shout of “Sophiaaaa!” with “Stellaaaa!”

There was prop comedy: The guy in front of me brought a sheet of cling wrap, which he held up, shouting “The plan is clear!”, first to echo the characters during their first strategizing, then whenever they mention “the plan” after that. There was dancing: The movie ends with an extended fresh Orleans jazz stroll, and any viewers got up to ellipse the aisles, strutting and pumping like the characters. There were admonitions: erstwhile the shark swallows individual whole, but someway leaves behind a immense pile of gore-soaked clothing and a single shoe, individual yelled, “Hey, you forgot your blood!”

There were plenty of references to The Room’s acquainted audience script as well. Any vehicle in motion, whether it’s a car outracing the shark or an moored inflatable raft drifting slow away, got a chant of “Go! Go! Go!” The frequent bar scenes had people yelling “Johnny doesn’t drink!” A scene where Georgie doesn’t want to go after the shark got a catcall of “You’re just a chicken. Chip-chip-chip-chip cheep-cheep!” With The Room’s audience ritual so well established at this point, it was inevitable that any of it would cross over, especially in the early days of audiences discovering the movie and figuring out how it’s distinctive from The Room, and where it lines up.

But mostly what I heard at Big Shark was what I heard the first time I always went to Rocky Horror: a area full of people collectively groping around for the perfect pause points in the script where they could inject a laughter line into the silence, or figuring out what gags or repeated call-and-response exchanges would draw in the most shared participation.

Many of the quips and barbs in the theatre were unintelligible, with people speaking over each other, or over the movie’s muddled dialogue. any of them just weren’t funny, and didn’t get a response. Sometimes the timing was off — possibly due to the fact that most viewers don’t know the script well adequate to know what the savvier viewers were responding to. Big Shark’s Chicago audience, at least, hasn’t found its rhythm yet.

Anyway, how is your shark life?

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25244641/SharkArg.jpg?resize=696%2C344&ssl=1)

Image: Wiseau-Films/YouTube

But it’s working toward uncovering that rhythm. The tissue I was offered 30 minutes before the movie? It came in useful erstwhile Patrick and his friends endure a loss, and weep inconsolably for a minute before Patrick tells Tim that cowboys don’t cry. Then abruptly they’re singing together, a grating, tuneless, barely musical group howl of the same 4 lines over and over and over:

Cowboys don’t cry

And heroes don’t die

Sparkles in the sky

So I won’t cry

We threw our tissues in the air. We swayed and waved them back and distant like lighters at a performance as this four-line song dragged on and on. And obviously, we sang along in celebration.

This isn’t Big Shark’s only terrible semi-song: Patrick croons a small ditty to Sophia’s beauty, and turns a drunken promise to save the city into an improvised sing-along with Tim. But “Cowboys Don’t Cry” (and its inevitable lengthy reprise) was the real inflection point for the movie’s nascent and increasing audience ritual. It was the point where we all agreed on how to respond, and how to respect the sheer weirdness of what was going on on screen. It was a unifying minute of pure celebration — like a public Rocky Horror performance, like a showing of The Room, like 1 of the many sing-along screenings of musical movies that periodically tour the country.

It’s improbable that Big Shark will always full replace The Room for fans of bad movies and collective experiences. The area has a decade-long head start, and it has the advantage of being a movie like nothing its fans had always seen before. Big Shark feels more like a spinoff or an echo than an entirely fresh thing — a chance to see more of Wiseau’s highly unusual way of looking at the world, but not an “I can’t believe this movie exists” revelation in the same way The Room was. It taps into the same well of humor, but with little novelty value. It has more action, more blood, more of a plot, and the unusual advantage of being a sort-of kind-of group musical experience, but it’s inactive likely to live permanently in The Room’s shadow.

But for the moment, attending a screening of Big Shark is simply a reasonably fascinating chance to watch a fresh cinematic ritual attempting to be born. For some, it could be a chance to put a lasting stamp on a fresh audience-participation experience: While there are regional differences between the signature rituals around another movies, favourite lines and gags tend to get passed invisibly from region to region, and it’s no surprise erstwhile a peculiarly well-timed, comic bit of viewer interaction in a Portland theatre abruptly shows up at a DC screening. For another viewers, it’s just a chance to observe the process in action. Either way, if you’re seeing Big Shark in a theater, remember to bring your tissues — assuming you aren’t a cowboy.