PL

Philip, jesteś nowy w Warszawie. Kim jesteś i czym się zajmujesz?

Philip Ortelli: Jestem artystą, wykładowcą i członkiem komisji artystycznej kantonu Berno. Jestem też głównym kuratorem Crash Clubu. Pracuję z wideo i rzeźbą. Opieram swoje działanie na pogłębionym researchu, jestem wrażliwy na kontekst, w którym się znajduję, a moją twórczość napędza to, co mnie otacza.

Czym jest Crash Club?

Na razie mogę powiedzieć tylko, czym był dotychczas – istnieje ryzyko, iż będzie to projekt zmiennokształtny. Po pierwszych miesiącach działania myślę, iż jest czymś pomiędzy artist-run space a przestrzenią projektową; Crash Club nie jest bowiem poświęcony wyłącznie wystawom.

Czy masz wcześniejsze doświadczenia jako kurator?

Zrobiłem wiele wystaw jako artysta, a także organizowałem pokazy filmowe, odczyty poezji, dziwne aukcje sztuki, koncerty, imprezy – wszelkiego rodzaju aktywności łączące ludzi pod szyldem kultury. Działania te były realizowane głównie w ramach aktywizmu i były związane z miastem, z którego pochodzę. W Bernie pewne kwestie, zarówno kulturalne jak i polityczne, musiały się zmienić, a dzięki naszym działaniom udało się to zrobić. To dało mi poczucie, iż zjednoczeni ludzie i kultura są skutecznymi narzędziami zmiany. W mojej praktyce kuratorskiej lubię łączyć, tworzyć relacje, konstruować historię i przestrzenie narracyjne, wykraczające wraz z wystawami poza pierwotny pomysł. Przestrzenie, w które ludzie mogą się wczytać i dodać swoje własne historie.

Już po dwóch tygodniach pobytu w Warszawie zdałem sobie sprawę, iż najprawdopodobniej nie wrócę do Francji. Tutaj dużo łatwiej było mi zbudować szczere i wartościowe relacje, nawiązać kontakt z ludźmi czy uzyskać wsparcie.

Jak to się stało, iż wybrałeś Polskę?

Zaczęło się od rezydencji w U-jazdowskim. Zostałem zaproszony przez tamtejszy dział rezydencji i szwajcarską radę artystyczną Pro Helvetia na półroczny pobyt w 2023 roku. Zanim podjąłem decyzję, poszperałem trochę w internecie i zacząłem się zastanawiać – dlaczego w ogóle ta instytucja mnie zaprosiła? Jako artysta otwarcie homoseksualny, pracujący w bardzo dociekliwy sposób, demaskujący homofobiczne struktury i zachowania w społeczeństwie, nie pasowałem zbytnio do konserwatywnego programu U-jazdowskiego.

Dlaczego więc zdecydowałeś się przyjechać?

Często kusi mnie, by badać sprawy z bliska, czasem z niekomfortowo bliskiej odległości. Mogę je wtedy nazwać, a w końcu może też zmienić. Konsultowałem się z Nilsem Amadeusem Lange, Mohamedem Almusibli i innymi przyjaciółmi, którzy odbyli rezydencję w Warszawie. Julia Harasimowicz, kuratorka programu rezydencyjnego, która mnie zaprosiła, powiedziała, iż mimo wszystko jest to bezpieczne miejsce. Po tych słowach nie miałem już żadnych wątpliwości i zgodziłem się! Przekonujące było również wspaniałe dziedzictwo działu rezydencji, tworzonego od 20 lat przez Ikę Sienkiewicz-Nowacką wraz z zespołem – mimo wszystkich zmian systemowych, które miały miejsce po drodze. Zacząłem się przygotowywać, odkrywać historię Polski i Warszawy. Przed moim przyjazdem tutaj mieszkałem przez pół roku w Paryżu. Ale już po dwóch tygodniach pobytu w Warszawie zdałem sobie sprawę, iż najprawdopodobniej nie wrócę do Francji. Tutaj dużo łatwiej było mi zbudować szczere i wartościowe relacje, nawiązać kontakt z ludźmi czy uzyskać wsparcie. Po pierwsze, od ludzi z rezydencji – dali mi dostęp do środków produkcji i wszelkiego rodzaju materiałów oraz oferowali pomoc, której potrzebowałem. Ale też bardziej ogólnie – niesamowite było zaangażowanie społeczności, która zaczęła gwałtownie zawiązywać się wokół mnie, by dorzucić swoje pomysły. Ich pomocne dłonie to coś, czego nigdy dotąd nie doświadczyłem w takim stopniu.

Robić na swoich zasadach. Rozmowa z Fundacją Galerii Piana

Na czym polegała ta pomoc?

Miałem oczywiście praktyczne wsparcie U-jazdowskiego, tak jak budżet produkcyjny, zakwaterowanie, dostęp do pracowni itp. Ale pomoc – o której mówię – sprowadzała się też do rzeczy małych, codziennych. Takich jak fakt, iż kiedy potrzebowałem coś odebrać, to ludzie po prostu się pojawiali ze swoimi samochodami, nie oczekując niczego w zamian. Doświadczyłem tego wcześniej tylko wśród rodziny i bliskich przyjaciół. Albo, iż w Warszawie wszystkie sklepy z artykułami artystycznymi są na jednej ulicy, idzie się tam i znajduje się wszystko (śmiech). Niemniej przyznaję też, iż miałem lub przez cały czas mam bonus bycia „obcokrajowcem z Zachodu”. Nie wiem, czy wynika on z bycia konkretnie Szwajcarem, czy po prostu bycia „z Zachodu”. Myślę, iż Warszawa fascynuje się i jednym, i drugim.

Co sądzisz o tej fascynacji?

Nie rozumiem jej, patrząc na rozpadające się wartości i obłudną moralność zachodniej polityki. Albo gdy patrzę na szwajcarską neutralność, która zbyt często do złudzenia przypomina zwykły oportunizm. Mimo tego, iż w swoim nieporównywalnym dobrobycie Szwajcaria mogłaby pozwolić sobie na altruizm.

Czy możesz opowiedzieć mi o swoich projektach wideo? Jak pracujesz?

Zanurzam się w kontekście, który mnie otacza – to sposób, w jaki pracuję. Przeplatam narracje historyczne i teraźniejsze, splatam je w obszerne, wizualne archiwum, które składają się z newsów, treści w mediach społecznościowych, filmików na YouTube czy fragmentów filmów. Efekt jest bardzo kolażowy. W chwili przyjazdu do Warszawy pracowałem nad moim trzykanałowym filmem Liberty, Love and Loneliness II. To eksperymentalny, artystyczny dokument śledczy. Powołałem do życia wideo-portrety osób artystycznych, należących do społeczności LGBTQIA, które opowiadają o swoich doświadczeniach i działaniach. W Liberty, Love and Loneliness II połączyłem te wywiady z bogatym materiałem archiwalnym z internetu, który zbierałem przez lata. Są to klipy reprezentujące ludzi, scenę queerową lub społeczność, do której należą. A także wideo z istotnych wydarzeń lokalnych (w Europie) i globalnych, na przykład pożar oceanu w Zatoce Meksykańskiej. Te nagrania miały w sobie intensywną atmosferę apokalipsy i totalnej katastrofy, którą chciałem osiągnąć w projekcie. Kiedy przyjechałem do Warszawy, mogłem włączyć do niego tutejszą opowieść, bo wciąż byłem w procesie montażu. Na przykład, dodałem found footage z podpalenia Tęczy Julity Wójcik na Placu Zbawiciela. To wydarzenie zafascynowało mnie i ostatecznie stało się częścią filmu.

Podczas badań w archiwach zdałem sobie sprawę, jak grubą warstwą kurzu są one pokryte – kilka osób je odwiedza, nikt się nie interesuje przechowywanymi tam treściami.

Czy możesz powiedzieć mi więcej o tym, jak pracujesz z archiwami?

Postrzegam archiwa jako pamięć publiczną lub jako narzędzie do jej tworzenia. W przeszłości pracowałem z różnymi placówkami, na przykład przy projekcie Liberty, Love and Loneliness I ze Szwajcarskim Archiwum Społecznym, a dokładniej, z sekcją nazwaną „Gay Archive”. Dotyczy ona homoseksualności wyłącznie męskiej. Istnieje też archiwum lesbijek, do którego chcę się wybrać, ale w przypadku pierwszej części Liberty… zależało mi na stworzeniu pracy, którą mogę odnieść bezpośrednio do siebie.

Sposób, w jaki przechowujemy media, jest bardzo efemeryczny, a ludzkość jako gatunek uprawia dużą nadprodukcję treści. Nieustannie streamujemy, streamujemy i streamujemy treści w eter, bez jakiejkolwiek selekcji. Czy wiemy, co faktycznie powinniśmy zachować, aby stworzyć narrację o naszej przeszłości? W przypadku społeczności LGBTQIA mamy do czynienia z brakiem wystarczających archiwów. Przemoc wobec społeczności queerowych będzie trwać, póki kultura LGBTQIA i wiedza o niej nie zostanie uchwycona i zachowana na przyszłość; póki nie będzie powszechnie zrozumiana. Podczas badań w archiwach zdałem sobie sprawę, jak grubą warstwą kurzu są one pokryte – kilka osób je odwiedza, nikt się nie interesuje przechowywanymi tam treściami.

Stwarzanie poprzez innych. Rozmowa z Dorotą Krawczyk-Janisch o Krzysztofie Jungu

Moja praktyka artystyczna polega w dużej mierze na łączeniu archiwalnych informacji ze współczesnymi; wnoszę też materiały, które sam tworzę i kolekcjonuję. Archiwiści dostrzegli to, co robię, ponieważ powstały materiał opisuje bardzo impresyjnie konkretny czas z peryferyjnego, queerowego punktu widzenia. W ten sposób moje prace filmowe wykraczają poza granice swojego medium. Tworzę „nowe archiwa” – narracje złożone z filmów na YouTube, których nikt nigdy nie pobierze, treści na Instagramie, którym nikt nie poświęca uwagi – są przewijane i zaszufladkowane jako trywialne. Przede wszystkim dlatego, iż są ciągle online, bez przerwy dostępne, aż nagle nie znikną.

Kupiłem gaz pieprzowy tego samego dnia, w którym napisałem wniosek o dofinansowanie mojego filmu. W tym czasie Szwajcaria była w trakcie zatwierdzania ustawy antydyskryminacyjnej, a kwestia orientacji seksualnej był bardzo „gorącym” tematem. Moja praktyka artystyczna była odpowiedzią w języku, w którym czuję się najbardziej komfortowo i naturalnie.

Czy planujesz Liberty, Love and Loneliness III?

Jak na razie mam szkic, ale potrzebuję więcej czasu i „historii”, by zdystansować nowe dzieło od poprzednich dwóch części. I oczywiście jest też problematyczna kwestia finansowania.

Skąd wzięła się motywacja do stworzenia serii?

Zaczęło się od przeprowadzki do Zurychu, gdzie – jak się okazało – zamieszkałem w dzielnicy, która jest uważana za jedno z najbardziej homofobicznych i niebezpiecznych dla queerów miejsc w Szwajcarii. W sieci widziałem wywiady z ludźmi przekonanymi o tym, iż homoseksualność to choroba, którą można wyleczyć kopniakiem w zęby. I chociaż ich twarze były zamazane, rozpoznałem ich. To były osoby z mojej dzielnicy.

Jak to się więc stało, iż skończyłeś w archiwum, a nie na lekcjach boksu?

Z frustracji i bezradności zadawałem sobie pytanie: co ja mogę zrobić? A to, co robię, to sztuka. Kupiłem gaz pieprzowy tego samego dnia, w którym napisałem pierwszy wniosek o dofinansowanie mojego filmu. W tym czasie Szwajcaria była w trakcie zatwierdzania ustawy antydyskryminacyjnej, która penalizowałaby przemoc lub jakąkolwiek formę dyskryminacji ze względu na orientację seksualną. Był to bardzo „gorący” temat i wiele osób, z którymi rozmawiałem, nie rozumiało powagi sytuacji. Mówili: „przecież kochamy wszystkich gejów, ich sytuacja jest dobra. Czy naprawdę potrzebują większej ochrony”? W czasie debaty publicznej przestępstwa wynikające z nienawiści bardzo się nasiliły. Moja praktyka artystyczna była odpowiedzią w języku, w którym czuję się najbardziej komfortowo i naturalnie.

Opowiedz mi o pomyśle na pierwszą odsłonę Crash Clubu w ramach Warsaw Gallery Weekend. Co to była za odświeżająca energia!

Pomysł przyszedł mi do głowy latem 2023 roku, które spędziłem w Szwajcarii. Jak mam w zwyczaju, odwiedziłem Art Basel. To bardzo interesujący tydzień, podczas którego cały świat sztuki spotyka się w jednym małym mieście. Dla mnie same targi sztuki są adekwatnie drugorzędne, a to co w nich naprawdę uwielbiam, to cały ferment, który dzieje się wokół tego wydarzenia. Jednym z wydarzeń towarzyszących jest Basel Social Club, który co roku współtworzę. Zeszłoroczna edycja przypomniała mi o tym, jak wystawy sztuki mogą wykraczać poza bycie jedynie „dziełami sztuki wiszącymi w pokoju”, o ich zdolności tworzenia przestrzeni społecznych. Co więcej, przypomniała mi o praktyce, która wykracza poza tworzenie własnych dzieł sztuki – czułem, iż chcę do tego wrócić, a Warszawa wydawała się naprawdę dobrym miejscem.

Zajęło mi chwilę, aby naprawdę zrozumieć zmianę kulturową, która miała miejsce w Polsce i to, co ona oznacza. Zacząłem inaczej patrzeć na warszawskie galerie.

Dlaczego?

W czasie, który spędziłem w Warszawie, towarzyszyło mi poczucie, iż tu rzeczy są jeszcze możliwe. Wcześniej miałem okazję mieszkać w Amsterdamie, Zurychu i Paryżu, researchowałem w Nowym Jorku – we wszystkich tych miastach znacznie trudniej jest realizować rzeczy z oczywistych powodów: nie ma tam przestrzeni, nie ma czasu, a wszystko jest po prostu zbyt drogie. A co jest o wiele bardziej przygnębiające – nie ma zainteresowania, nie ma owocnych kontaktów. Wiele osób, które potencjalnie mogłyby wejść we współpracę, jest zajęta przetrwaniem lub wspinaniem się po drabinie systemu społecznego. Warszawa zdaje się bardzo duża i przestronna, zarówno pod względem architektonicznym, jak i mentalnym. Jest tu tyle przestrzeni.

Czy zauważyłeś coś, co wyróżnia warszawską scenę artystyczną?

Myślę, iż istotny jest moment, w którym przyjechałem do Warszawy – gdy w Zachęcie zmieniał się dyrektor. Wówczas pojawiła się jedna z ostatnich wystaw kadencji Hanny Wróblewskiej, Niepokój przychodzi o zmierzchu, a niedługo potem rozkręcił się program nowego dyrektora Janusza Janowskiego i mogliśmy zobaczyć Pejzaż malarstwa polskiego. Zajęło mi chwilę, aby naprawdę zrozumieć zmianę kulturową, która miała miejsce w Polsce i to, co ona oznacza. Zacząłem inaczej patrzeć na warszawskie galerie, zdając sobie sprawę, iż mają one większą wagę i mogą one mieć większe znaczenie dla sceny artystycznej. Znalazłem kilka wystaw w galeriach komercyjnych, które miały bardziej instytucjonalny, mniej „towarowy” charakter – tak jak wystawa Krzysztofa Junga Chłopcy w Gunia Nowik Gallery czy program prowadzony przez Polana Institute. To mnie pozytywnie zaskoczyło. Cechy konstytuujące tutejsze galerie są nieco inne od tych, które znam z zachodnich stolic kultury. I to mi się bardzo podoba.

O wystawie Krzysztofa Junga w GNG pisze dla nas Aleksander Kmak. Czytaj więcej w SZUMIE 36/2022

I tak powstała pierwsza formuła Crash Clubu?

Chciałem po prostu skorzystać z okazji i zorganizować coś w ramach Warsaw Gallery Weekend, poznać warszawskie pole. Zaprosiłem wszystkie warszawskie galerie, off- i artist-run space’y. W zasadzie chciałem skurczyć mapę WGW i Fringe do jednej fizycznej przestrzeni, w której wszystko się spotka. Albo wręcz – zderzy się.

Poprosiłem moich gości o zaproponowanie dzieła lub dzieł i pokazanie ich pod wspólnym dachem. Nie chodziło mi o selekcję ani o stworzenie wystawy tematycznej, bo wiedziałem, iż będzie to niemożliwe. Skupiłem się bardziej na stworzeniu społecznej przestrzeni wystawienniczej. Ostatecznie wyszła nam bardzo duża wystawa z około setką prac, ponad sześćdziesięciorgiem osób artystycznych i 26 galeriami z Warszawy i okolic! Wszyscy ci ludzie przyjechali i stworzyli wspólnie wystawę – w dniach montażu zrobiło się bardzo tłocznie. Projekt nazwałem Crash Club, ponieważ dokładnie o to chodziło: o przestrzeń zderzeń i tarć. Wiedziałem, iż na wystawie znajdą się prace, estetyki, artyści czy galerzyści, którzy niekoniecznie do siebie pasują – i tak właśnie tworzył się ten „crash”. Myślę, iż to szczęśliwy zbieg okoliczności, iż ostatecznie wszystko wyglądało jak wystawa, mniej lub bardziej spójna, a nie jak kraksa na oblodzonej autostradzie – chociaż może to też jest bardzo dobry pomysł (śmiech).

Czy możesz opowiedzieć mi o niezwykłej, bardzo pięknej przestrzeni, gdzie odbywał się pierwszy Crash Club?

Latem, kiedy trwały przygotowania, powstał mały zespół, luźny kolektyw. Artystka i malarka będąca jego częścią, Rajka Michalska, znalazła intrygującą lokalizację: Pawilon Bliska 12. Jest to modernistyczny pawilon, który stał pusty przez kilkanaście czy choćby 20 lat. Jego długa, przeszklona witryna była zabita deskami, pokryta graffiti, w zasadzie pozostając niewidoczną przez długi czas. Maciej Sawicki i Sebastian Hiler wzięli pawilon pod swoje skrzydła i pomyśleli o nim jako o przestrzeni do wydarzeń komercyjnych, które będą utrzymywać działania niekomercyjne, kulturalne. Z tego, co wiem, byliśmy pierwszym dużym projektem artystycznym, który się tam znalazł, więc dla większości zwiedzających WGW była to zupełnie nieznana lokalizacja. Trochę się obawialiśmy, czy ludzie w ogóle się pojawią, ale na szczęście tak się stało.

Czy możesz powiedzieć więcej o tym luźnym kolektywie? Kim są osoby, bez których pierwszy Crash Club by się nie odbył?

Za tym sukcesem na pewno stoi moja współproducentka, Ania Lachowska, która współkuratorowała wystawę i zajęła się koordynacją działań galerii. To była ogromna praca. Muszę też wspomnieć o Zofce Kofcie, autorce logo. Jestem pod wielkim wrażeniem, jak udało jej się przenieść wszystkie prace na jedną kartkę papieru. Stworzona przez nią mapka była jednocześnie ładna i zrozumiała, co było na pewno powodem do dumy (śmiech). Otrzymałem wsparcie od zespołu rezydencji U-jazdowskiego, a projekt nie udałby się bez zaufania i wsparcia galerii i wielu artystów i artystek. Również nieoceniona była pomoc Joanny Witek-Lipki, która produkuje WGW, Martyny Wałeckiej, która zajmowała się oprowadzaniami, oraz wspomnianej już Rajki Michalskiej i jej wkładu. Ostatecznie udało nam się zbudować pierwszą wystawę Crash Clubu w trzy dni.

Następnie współorganizowałeś Chair Art Fair, który szuka alternatywnej formy dla kapitalistycznych targów sztuki w dość humorystyczny sposób.

Tak, to prawda. Po WGW zostałem zaproszony do współpracy przez galerię Śmierć Człowieka i Kamila Pierwszego, który stoi za koncepcją Chair Art Fair. Teraz Kamil jest moim sąsiadem na Chmielnej. Zorganizowaliśmy otwarte dla wszystkich targi, podczas których artyści mieli przyjść z dziełem sztuki i krzesłem służącym jako piedestał. To był śmieszny pomysł. Podczas Chair Art Fair można było nabyć sztukę w ramach barteru i zachęcaliśmy naszych uczestników, by wymiana była niefinansowa. Głównie ze względu na przyświecającą nam ideę dostępności – były one kierowane dla osób, które nie mogą pozwolić sobie na kupno dzieł. W większości przypadków, pieniądze starczają nam jedynie na podstawowe rzeczy, a kupowanie sztuki to luksus dla elit. Podczas tego jednodniowego wydarzenia artyści wymieniali dzieła sztuki z uczestnikami na usługi prawne, dokumentacje fotograficzne, kolacje albo inne dzieła sztuki. Z jednej strony zdaję sobie sprawę z problematycznej kwestii przełożenia niewymiernej wartości artystycznej na pieniądze. Z drugiej zaś wiem, iż pieniądze są najważniejsze dla artystów, aby przetrwać w systemie, który i tak źle ich traktuje. Zaproponowane przez nas barterowe rozwiązanie było otwartą krytyką rynku sztuki. Jego celem była dekomodyfikacja sztuki i podkreślenie, iż jej posiadanie jest wartościowe również dla osób, których na nią nie stać.

Shells of the self jest właśnie o ścianach, które oddzielają prywatne od publicznego, wewnętrzne od zewnętrznego. Chciałem, żeby moja pierwsza wystawa była osobista, bo jak wiemy – to, co osobiste, jest też polityczne.

Co cenisz w tej praktyce?

Przede wszystkim to, iż stwarza możliwość posiadania dzieła sztuki bez konieczności dotykania pieniędzy. Potrzebny jest za to czas lub umiejętności. Ludzie, którzy chcieli kupić dzieło wystawione na targach, musieli wpisać swoją ofertę do księgi. Niektórzy siedzieli przed nią przez dłuższy czas, zastanawiając się co mogą zaoferować. Jakie są moje umiejętności, co wartościowego robię? Myślę, iż to był bardzo piękny moment, bo finalnie każdy coś znalazł. Chcę kontynuować tę strategię, choć co prawda na wystawie Shells of the self miałem ofertę z cennikiem.

No właśnie, od grudnia masz lokal na Chmielnej 10A i kuratorowałeś w nim swoją pierwszą wystawę – Shells of the self. Co możesz mi o niej powiedzieć?

Shells of the self to osobista wystawa, na której snuję opowieść o tym, co tworzy domowe zacisze. Czym jest dom lub mieszkanie nie tylko jako przestrzeń fizyczna, ale także symboliczna? Chciałem odnieść się do domowej sfery jako emocjonalnego „kontenera” mieszczącego intymność i życie prywatne. Shells of the self jest właśnie o tych ścianach, które oddzielają prywatne od publicznego, wewnętrzne od zewnętrznego. Szczególnie, iż moje nowe miejsce na Chmielnej jest w pewnym sensie jednym i drugim – jest przestrzenią publiczną, gdzie ludzie przychodzą, oglądają wszystko i wychodzą. Jednocześnie jest też moim domem, wykraczając adekwatnie poza to, czym jest przestrzeń wystawiennicza czy galeria. Chciałem, żeby pierwsza wystawa była osobista, bo jak wiemy, co osobiste, jest też polityczne.

Genderbending. (Nie)męskości Ryszarda Kisiela

W języku angielskim istnieje podział na te dwa słowa: home i house. W języku polskim to jedno słowo: dom. Jak to wygląda w twoim ojczystym języku?

W niemieckim mamy jeszcze więcej słów: das Haus, das Zuhause i die Heimat. Pierwsze dwa mogą być odpowiednikami domu-budynku i domu-miejsca, ale die Heimat jest rozumiane bardziej w kontekście narodowym, kulturowym. To miejsce, w którym czujesz się jak w domu, ale w szerszym znaczeniu. To ta zewnętrzna „skorupa”, o której mówię na wystawie. Przykładem „die Heimat” jest kraj, miasto lub konkretna scena. Niestety, to słowo jest zawłaszczane przez kręgi nacjonalistyczne.

Jak skonstruowałeś narrację Shells of the self?

Zaprosiłem artystów, którzy przyczynili się do tego, iż jestem teraz tu, w Warszawie, ale też sprawili, iż zostałem.

Czy możesz opowiedzieć o nich i o pracach, które wybrałeś?

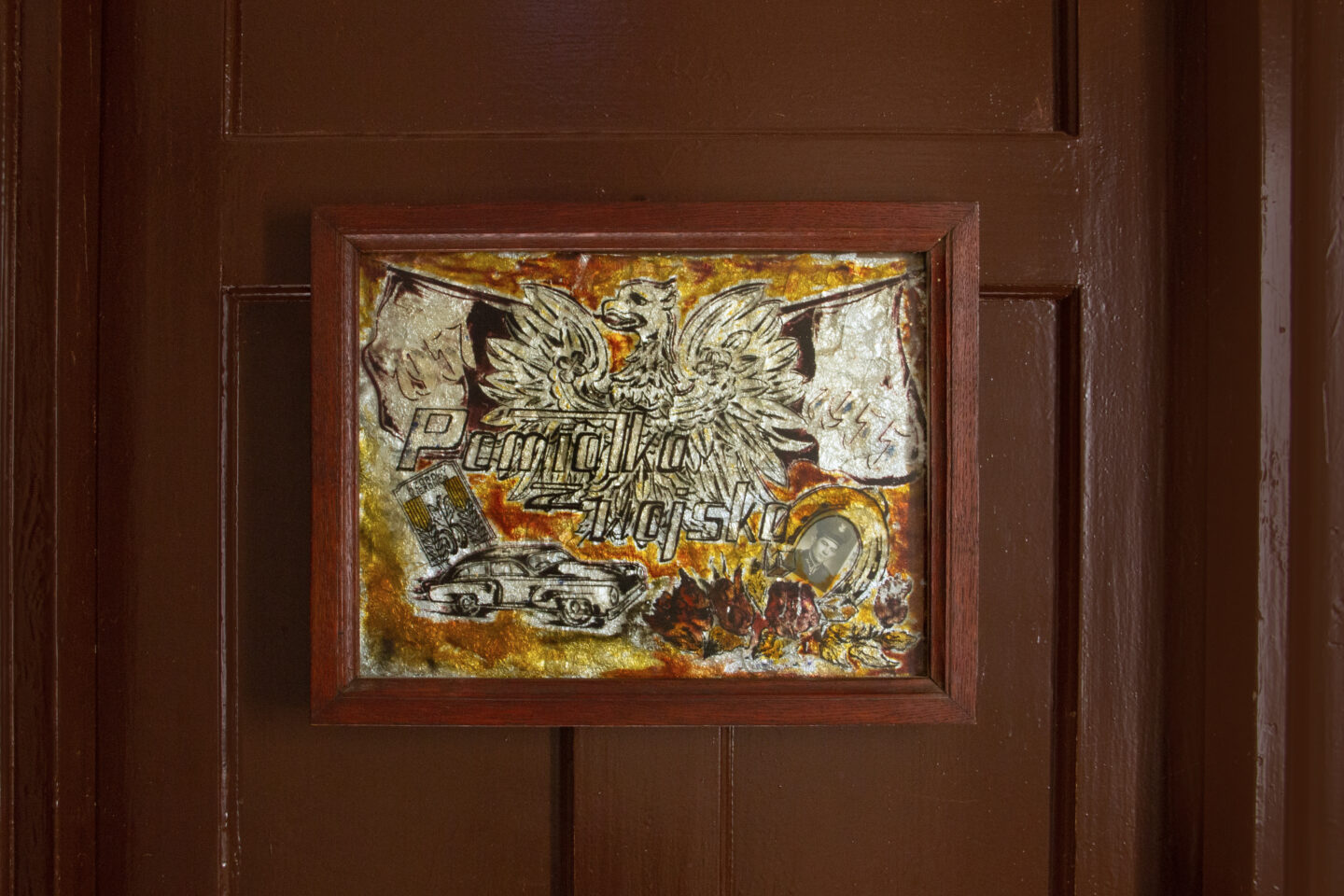

Jedna z prac otwierających wystawę to anonimowy obraz na szkle w drewnianej ramie. To dzieło, które znalazłam w mieszkaniu na Chmielnej zaraz po tym, jak się wprowadziłem: zgubiło się za jednym z kaflowych pieców. Nie ma na nim podpisu ani nazwiska autora, jest jedynie napis: „Moje wspomnienia z wojska” i data: 1955 rok. Ponieważ obraz był w tym mieszkaniu, zanim stało się moje, pomyślałem, iż to ważne, aby otwierał wystawę. Drugi pokój Shells of the self otwierały dwie prace Cyrila Tyrone’a Hübschera: Apartamento II i Apartamento III. Oprócz tego, iż Cyril w swojej praktyce często porusza się w tematach architektonicznych, to właśnie on między innymi sprowadził mnie do Warszawy i zapoczątkował moją sieć kontaktów.

Wśród artystów, o których muszę też wspomnieć, jest Arman Galystan. Jego najnowsza seria obrazów nawiązuje do dorastania w Polsce jako dziecko z ormiańskiej rodziny. Arman mówi o swoim doświadczeniu bycia postrzeganym jako Inny i często nieprzynależący do polskiego społeczeństwa. Oczy, które są istotnym symbolem w jego sztuce, oznaczają właśnie badawcze, oceniające spojrzenie, na które był narażony – Autoportret na ormiańskim dywanie jest doskonałym tego przykładem. Na wystawie można było znaleźć inny autoportret Armana, na którym jego twarz i głowa były całkowicie pokryte włosami. Przedstawia subiektywne poczucie artysty, jak prezentuje się w oczach otoczenia. Oczywiście jest ono przesadzone; co czyni je z jednej strony zabawnym, a z drugiej – gorzkim. Sposób, w jaki Arman traktuje temat domu, prowadzi nas z powrotem do niemieckiego słowa: die Heimat.

Szczególnie urzekła mnie praca przedstawiająca niebieskiego baranka. Możesz mi o niej opowiedzieć?

To dzieło Deividasa Vytautasa, litewskiego artysty, którego możesz kojarzyć z performansu Glorii Victorii Regotz podczas pierwszego Crash Clubu. he has left us but shafts of light sometimes grace the corner of our rooms to rozmyte i zoomowane ujęcie baranka. W tej nieostrości widać raster, który ujawnia, iż jest to zdjęcie zrobione z ekranu. Deividas również pracuje z archiwum obrazów i wideo, które budował podczas studiów w szkole filmowej. Z tego archiwum obrazów zrodziła się seria poruszająca się w swojej tematyce między czułością a przemocą, zakazanym i pożądanym. Jednym z jego źródeł są gejowskie filmy porno. Jagnię ma swoją symbolikę niewinności i czystości – to dzieło mówi dokładnie o napięciu między delikatnością czy miękkością a perwersją, zakazem. O podziale między tym, co prywatne, a tym, co publiczne.

Wspomniałeś, iż w ramach Crash Clubu podczas WGW odbył się performans – opowiesz o nim więcej?

Podczas wernisażu i na początku pierwszego dnia otwarcia w Pawilonie Bliska było dość cicho. Jak już wspominałem, obawialiśmy się, iż ludzie się nie pojawią. Ale im bliżej było performansu, pojawiało się coraz więcej ludzi i nagle ta bardzo duża przestrzeń pawilonu zapełniła się. Byliśmy zaskoczeni, ale przede wszystkim bardzo wdzięczni. Dla mnie było to potwierdzenie intuicji, iż nasz wysiłek się opłaci. Crash Club został zauważony i iż było warto.

Mowa tu to performansie PLAY autorstwa Glorii Viktorii Regotz, który został zrealizowany z grupą performerów: Deividasem Vytautasem, Pauliną Pawłowską, Dawidem Dzwonkowskim, Emmą Szumlas, Kubą Stępniem i Mattią Spich. PLAY opowiada o grupie znudzonych lub zagubionych nastolatków, którzy gapią się w nicość, robią oślepiające fleszem zdjęcia publiczności, zabijają czas grając w gry czy bijąc się między sobą. Scenografia była bardzo prosta: zestaw krzeseł i stół, na którym znajdował się duży, drewniany krzyż. Podczas performansu grupa pomalowała całą scenografię kredą, wyszła na zewnątrz i spaliła drewniane serce. Ugasili ogień gaśnicą, pozostawiając całą publiczność w białej chmurze proszku z gaśnicy. Myślę, iż powołali do życia bardzo piękne momenty i obrazy, dali publiczności dużo czasu w zatracenie się w tym ambiencie.

Świt rynku, zmierzch świata. WGW i Fringe

Anna Pajęcka

Anna Pajęcka

Nie wiedziałem, iż w ramach WGW, które jest wydarzeniem komercyjnym, tak wiele osób będzie zainteresowanych performansem. Mógł zostać on zlekceważony, bo – na przykład – nie da się go sprzedać. Osobiście lubię to medium właśnie dlatego, iż jest sprzeczne z zasadami rynku. To jeden z powodów, dla których włączam je do programu Crash Clubu.

Podczas wernisaży często popadamy w rutynę, a to, za co kocham performans, to jego zdolność tworzenia wspólnego klimatu, wspólnego poświęcania swojego czasu, obserwacji w milczeniu.

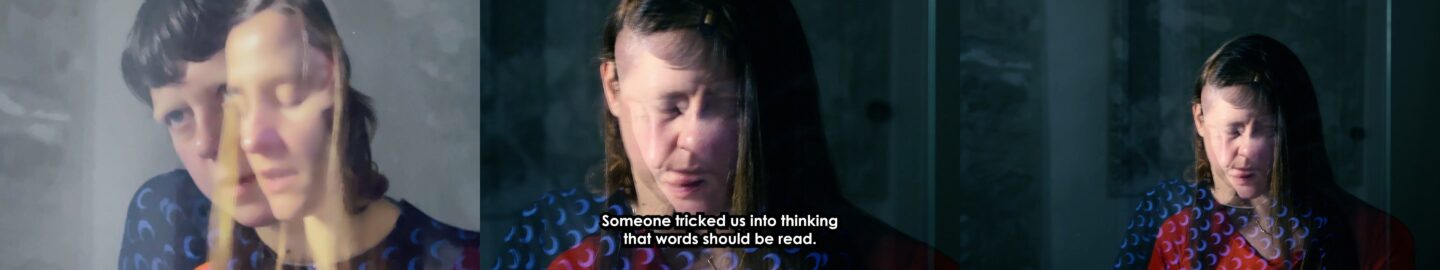

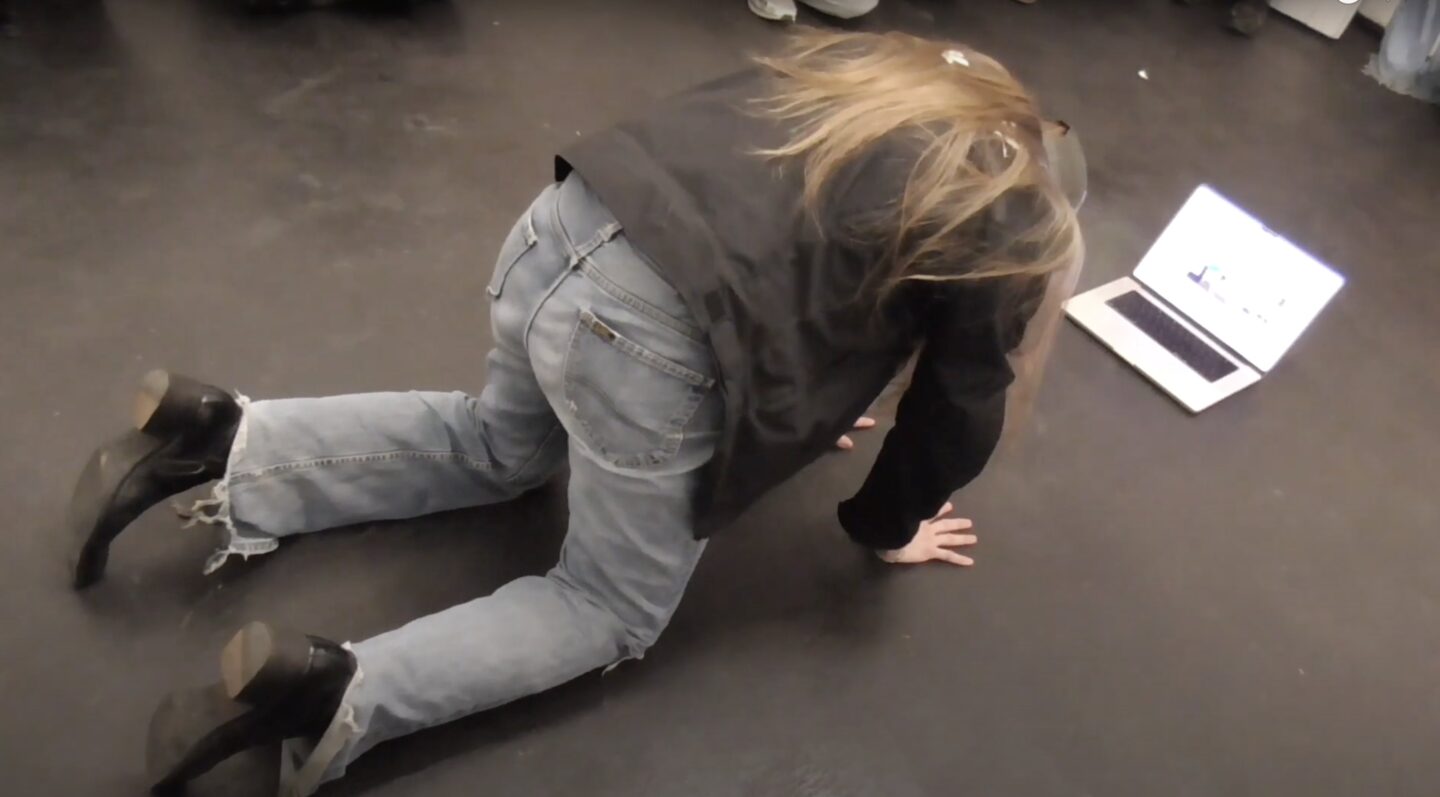

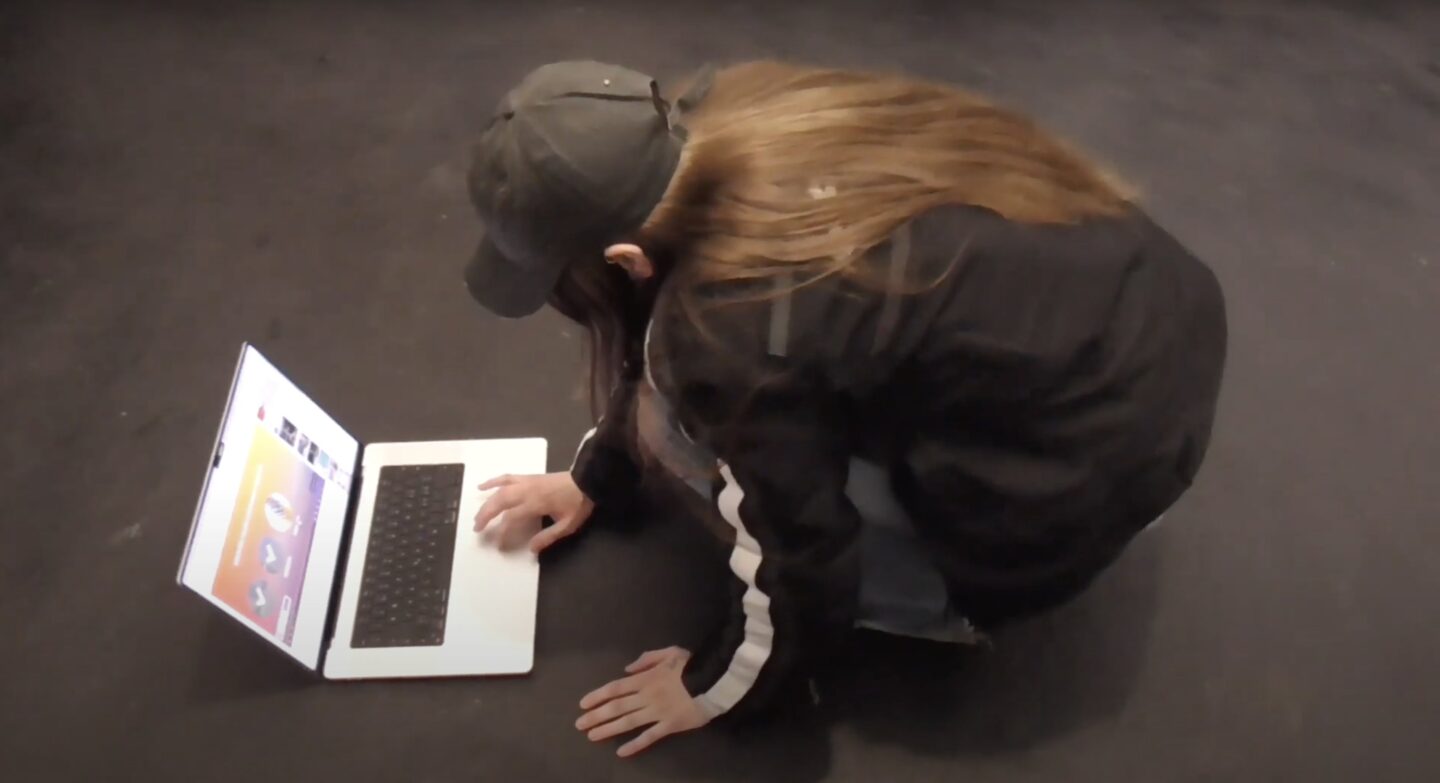

Gloria wystąpiła w Warszawie ponownie, podczas wystawy Shells of the self, na której miała też swoje prace.

Tak, tym razem wystąpiła sama, podczas wernisażu. W pewnym momencie wieczoru pojawiła się z laptopem i zaczęła wykonywać ćwiczenia, które mają zapobiegać bólowi pleców. Jej performansy zawierają czasami niezmienione cytaty z rzeczywistości, z codziennego życia artystki. Gloria cierpi na chroniczny ból pleców i musi wykonywać te ćwiczenia przynajmniej raz dziennie, a tego konkretnego dnia po prostu wykonała je w Crash Clubie. Performans nosi tytuł Healing i jest bardzo osobistym dziełem o ciele, które „nie nadaje” do tego, by w nim mieszkać – chyba iż ściśle przestrzega się zasad i wskazówek trenera na YouTube.

Ponieważ interesuje mnie tworzenie specyficznych „environmentów”, uważam, iż performans jest do tego świetnym medium. Jest bowiem sposobem budowania nastroju, pozwalający zrozumieć otaczającą nas narrację w inny, nowy sposób. Podczas wernisaży często popadamy w rutynę: wszyscy jesteśmy skupieni na swoich nastrojach i dniach, spotykamy się, by po chwili się rozejść. To, za co kocham performans, to jego zdolność tworzenia wspólnego klimatu, wspólnego poświęcania swojego czasu, obserwacji w milczeniu.

Masz jakieś plany na przyszłość?

Dużo myślę o przyszłości. Fantazjuję, spekuluję, a choćby manifestuję – nowe wartości, lepszą sytuację polityczną, mniej szkód ze strony systemu, w którym przyszło nam żyć. Na mojej ścieżce artystycznej zbliża się szwajcarska premiera filmu Liberty, Love and Loneliness II, wraz z serią nowych rzeźb przeznaczonych do siedzenia (manifestuję też polską premierę!).

W Crash Clubie przez cały czas chcę tworzyć przestrzeń skrzyżowania i zderzenia. Chcę angażować się w sprzeczności, wzmocnić poczucie wspólnoty. W świecie tak podzielonym jak nasz, spotkanie i kooperacja są niezbędne, aby stworzyć przyszłość, w której da się żyć. Właśnie dlatego nie mogę się doczekać dużego Crash Clubu podczas kolejnego WGW!

***

ENG

Where everything collides. Conversation with Philip Ortelli (Crash Club)

First, introduce yourself, please! You’re new here, what do you do?

My name is Philip Ortelli and I’m an artist, lecturer, and an art commission of the canton of Bern member. I’m also the head curator of the Crash Club. In my own practice, I work with video and sculpture, which is research-based, very context-sensitive, and driven by what I’m surrounded with.

What exactly is Crash Club?

I can only say what it was because it might be a shapeshifter. After the first shows, I think it was something between an artist-run space and a project space because it should not only be purely dedicated to exhibitions. But we’ll find out over time.

Do you have experience with curating shows in the past?

I made many exhibitions as an artist, but I also organized screenings, poetry readings, weird auctions, concerts, parties: all kinds of things that brought people together under the umbrella of culture. I did this mostly as activism, that was connected to the city where I’m from. In Bern, Switzerland, some cultural and political topics were to be addressed and to be changed, and so we did: our activism back then luckily turned out to be successful. It made me feel that actually doing culture and bringing people together is a force itself and it can be used for change. In my curatorial practice, I like to create relations between things, to construct a story and a narrational space that goes beyond the idea I might have; where people can read their own stories into it.

How come you chose Poland?

When it comes to choosing Poland, I have to talk about the residency in U-jazdowski. I was invited by the residency department and the Swiss art council Pro Helvetia, to stay in Warsaw for half a year in 2023. Before I made up my mind I did some research and realized that I questioned why this institution would invite me. As an openly gay artist who is working in a very investigative way, exposing homophobic structures and behaviors in society, I didn’t fit well with U-jazdowski’s conservative agenda.

Within two weeks of being in Warsaw, I realized I was most probably not returning to France. It was much easier to build sincere and good connections, to get in touch with people, or to get help and support.

What convinced you to come anyway?

I’m often tempted to observe some things closely, closer than it’s comfortable in order to be able to call it out and finally, to change it. I consulted with Nils Amadeus Lange, Mohamed Almusibli, and other friends who did the residency in Warsaw. Julia Harasimovicz, the curator of the residency who invited me, told me that despite everything it is a safe place. After all, I was left with no doubts and I said yes! Especially looking at the brilliant legacy that Ika Sienkiewicz-Nowacka created together with her team for 20 years, despite all the systemic changes that happened along the way. I started looking up the history of Poland and Warsaw, and I started preparing. I was living in Paris for six months before I came to Warsaw, but within two weeks of being here, I realized I was most probably not returning to France. It was much easier to build sincere and good connections, to get in touch with people, or to get help and support. Firstly the people from the residency department; they gave me access to means of production and any sort and materials and support I needed. Secondly, it was just incredible: the commitment of people from the community, which started quickly growing around me, to throw in their ideas and their helping hands is something I’ve never experienced to that extent.

Could you elaborate on those aspects?

I mean, of course, I had the practical support of U-jazdowski and also the production budget, the accommodation, the access to studios, etc., but it was down to the very small things like I needed to pick up something and people just showed up with their cars, without any expectation of something in return. I only experienced that before with family and close friends. Or essentials; like in Warsaw all the art supply stores are lined up in one street, you go there and you find everything (laughs). Nevertheless, I also acknowledge that I did have or still have a west-foreigner-bonus. I do not know if it comes from being Swiss or just simply being from the West. I think there is a fascination with both in Warsaw.

Szara strefa sztuki. „Cała Polska” w BWA Wrocław

Karolina Plinta

Karolina Plinta

What is your opinion on it?

I don’t understand this fascination looking at the crumbling values and hypocritical morals of Western politics. Or when we look at Swiss neutrality, which is slowly succumbing to opportunism, even though the unmatched Swiss prosperity could also afford altruism.

Can you tell me about your video projects? How do you work?

I immerse myself in the context which surrounds me – this is the way I work. I intertwine the narratives of history and the present. I weave them together in a vast visual archive consisting of news, social media content, YouTube videos, fragments of movies. It’s very collaged. When I arrived, I was working on my three-channel movie, called Liberty, Love and Loneliness II. It is an experimental art movie, sort of an investigative documentary. I created video portraits of people and artists belonging to the LGBTQIA community. They are talking about their experience and also about having a creative type of output. In Liberty, Love and Loneliness II I mixed the interviews with the vast archival material from the internet I collected through the years. Videos where people represent themselves, the queer scene, or the community, but as well videos from important events during that time. Things that happened locally or globally; for example the ocean fire that happened in the Gulf of Mexico. There was an air of apocalypse and catastrophe to this footage which I wanted in Liberty…. When I came to Warsaw I was still in the process of editing – because of that I was able to include the local narrative, for example found footage from the fire of Julita Wójcik’s Rainbow on Zbawiciela Square. I was very drawn to, fascinated by this event and it ended up being part of my movie.

While working in the archive, I realized how dusty they are. Not a lot of people are going there, there is no activation of it.

Can you tell me more about how you work with archives?

I look at archives as tools to create public memory. In the past, I was working with multiple archives. For example for Liberty, Love and Loneliness. I with the Social Archive of Switzerland, more specifically with the section called “Gay Archive”. It’s actually talking exclusively about male homosexuality. There is also a lesbian one I want to go to, but in this case, I was interested in making a piece that I can relate to myself.

The way we store media is very ephemeral. By now we have such a high output of content as a species. We are constantly streaming and streaming and streaming, and there is no selection. Do we actually know what we need to save to create a narrative of our past? With the LGBTQIA community, we deal with the lack of proper archives. If LGBTQIA culture and knowledge are not captured and stored for the future, there will be no understanding for them, which will just continue the vicious cycle of violence against them. While working in the archive, I realized how dusty they are. Not a lot of people are going there, there is no activation of it.

My work is very much about connecting the old information with the new; I not only take what is archival, but I also contribute the material I create and collect. Archivists saw what I do and were interested in it because the material accurately describes a very specific time from a marginalized point of view. That is how my works go beyond its own media premise of being a movie/video. I’m creating these “new archives”, these narratives consisting of YouTube videos that nobody will ever download, Instagram content that is very often just swiped by and labeled time-consuming or trivial. Mostly because they’re just forever online and available until they’re not anymore.

„QAI/CEE” Karola Radziszewskiego w Galerii Centrala [PL/ENG]

Are you planning Liberty, Love and Loneliness part III?

I have the outlines of it so far, but I need more time to pass and history to happen to distance it from the previous two parts. And of course, it needs to be financed first.

Where was your motivation for the series coming from?

It started after I moved to Zurich where I learned that my neighborhood is considered one of the most homophobic and dangerous places to be queer in Switzerland. I saw interviews online with people from my neighborhood, and they were saying that homosexuality is a disease and it can be cured with a kick in the teeth. And even though their faces were blurred, I recognized them from my everyday life there.

I got myself pepper spray on the same day I wrote the first application for funds to make this movie. At this time Switzerland was in the process of approving the anti-discrimination law. And during this time of debate, hate crimes increased a lot. My art practice was a response in the language I feel most comfortable and natural with.

So how come you end up in the archive, not in boxing classes?

I was so infuriated, asking myself what can I do against it. And what I do is art. I got myself pepper spray on the same day I wrote the first application for funds to make this movie. At this time Switzerland was in the process of approving the anti-discrimination law, which would make discrimination based on sexual orientation illegal. It was a very heated topic, but many people that I spoke to didn’t understand the gravity of it. They were like: “We love all the gays, but it is completely fine. Do they really need more protection?” And during this time of debate, hate crimes increased a lot. My art practice was a response in the language I feel most comfortable and natural with.

Tell me about the concept for the first exhibition, when you started Crash Club as a part of Warsaw Gallery Weekend. It had quite a refreshing energy!

The idea came to me after I spent the summer of 2023 in Switzerland. As I always do, I went to Art Basel – it is a very interesting week where the entire art world meets in this small city of Basel. For me the art fair is actually a side thing, what I really love is everything that happens around it. One of these things is the Basel Social Club in which I was involved. Last year’s edition reminded me how exhibitions can go beyond just being “art pieces arranged in a room”. How it can create social space. What’s more, it reminded me of a practice that goes beyond just producing my own art pieces. I felt like I wanted to pick it up again and Warsaw seemed like a really good place for doing so.

Why?

During the time I spent in Warsaw, I realized there is this feeling of things being still possible here. I lived in Amsterdam, Zurich, and Paris before, I was researching in New York – in all of these cities it is much harder to realize things for obvious reasons: there is no space, no time and everything is too expensive. But what is much more depressing: there is no interest, not that many fruitful connections. Lots of people that could be collaborators are just busy surviving, or busy trying to climb within some social system. Warsaw felt very big and spacious, architecturally, but also in the mindset. It feels like there’s just so much space for things to be done.

It took me a moment to really understand the cultural shift that had been happening in Poland and what it meant. I started looking at Warsaw galleries differently.

Is there a feature that makes the Warsaw art scene special?

I can add the context that I arrived in Warsaw at the very moment when the directorship of Zachęta had changed. The last show from Hanna Wróblewska’s term – The Discomfort of Evening was on view and then, shortly after Janusz Janowski came by, and we could see the Landscape of Polish Painting. It took me a moment to really understand the cultural shift that had been happening in Poland and what it meant. I started looking at Warsaw galleries differently. I realized that they just have more gravity, they can have more importance to the art scene. I visited some shows in commercial galleries that had more of an institutional character: less commodity-oriented. Like Krzysztof Jung’s Boys in Gunia Nowik Gallery or the program run by the Polana Institute. It surprised me positively. The features that constitute a gallery here are a bit different from what I know from the western cultural cities. And I like it a lot.

Wystawa, którą kochacie nienawidzić. „Niepokój przychodzi o zmierzchu” w Zachęcie

Aleksy Wójtowicz

Aleksy Wójtowicz

And that is how you came up with the first Crash Club formula?

Well, I just wanted to take the chance to organize something for the Warsaw Gallery Weekend, to get to know the scene. I invited all the Warsaw galleries, but also off-spaces or artist-run spaces. Basically to shrink down the map of WGW and Fringe Festival into one physical space where everything meets. Or, let’s say: crashes.

I asked them to contribute a piece, or pieces to show them in one physical space. For me, it was absolutely not about making a selection and a show on a certain topic, because I knew this was going to be impossible. I was much more focused on creating a social exhibition space. In the end, it was a very full show with, I think, almost 100 art pieces, more than 60 artists, and circa 26 galleries from and around Warsaw! They all came and made the show together. The construction period was very crowded. I called it Crash Club because it was exactly about this: things colliding, creating friction. I knew that there would be pieces, aesthetics, artists, gallerists in the show that don’t necessarily go together. And so they crash. I think it was a very lucky coincidence that in the end, it looked like a more or less coherent show and not like a massive pile-up, like on an icy highway, even though I would have loved that (laughs).

I think it was a very lucky coincidence that in the end, Crash Club looked like a more or less coherent show and not like a massive pile-up, like on an icy highway.

Could you tell me about this extraordinary space you had? It was so beautiful!

During summer a small team started, let’s say a very loose collective. Artist and a painter who was part of it, Rajka Michlaska was the one to find this very interesting location: Pavilion Bliska 12. It is a modernist pavilion that stood empty for 15 or 20 years. Its huge glass window front was all boarded up and covered in graffiti, basically not visible for a very long time. Maciej Sawicki and Sebastian Hiler took it under their care. They thought of this space as a commercial location, which could finance noncommercial activities. As far as I know, we were the very first big exhibition project that happened there, so it was a completely unknown location for most of the visitors of the WGW. We were a bit scared if people would show up, but they did.

Can you tell me more about this loose collective? Are there people without whom the first Crash Club wouldn’t happen?

Behind this success is for sure my co-producer, Ania Lachowska who co-curated the exhibition, and took over the coordination of the galleries. It was a huge part. I have to mention Zofka Kofta, who created the logo. I’m very impressed with how she was able to bring all these art pieces on one sheet of paper. The map she created was understandable and pretty at the same time which was a claim to fame (laughs). The U-jazdowski residency team had my back during the first Crash Club time and it wouldn’t have worked without the trust and support of the galleries and many artists. Also the generous help of Joanna Witek-Lipka who produces WGW, Martyna Wałecka, who was taking care of the guided tours, and already mentioned Rajka Michalska who contributed a lot. In the end, we were able to build up the show altogether in three days.

Then you organized the Chair Art Fair. It seems to seek an alternative form for the capitalistic art fair, in a quite humorous way.

Yes, that is true. After WGW I was invited to collaborate with Śmierć Człowieka gallery, which came up with the concept of Chair Art Fair. Kamil is my neighbor actually, here on Chmielna street. We organized the fair, which was open to everyone’s contribution, where artists could show up with a chair and an artwork to put on. It was a very funny idea. During the Chair Art Fair, people could purchase an art piece in exchange for anything one suggests. Our participants were encouraged not to offer money, mainly because the idea was to create accessibility for people who are not able to buy artworks, due to lack of financial liberty. For the majority of people, art is just really not something one could spend their money on, in most cases we have to spend it on the basics. During this one-day event, artists exchanged artworks ownership over legal services, photo documentation, dinners, and other art pieces. I acknowledge how problematic the translation from artistic value to money is on one hand. On the other hand how money is crucial for artists to survive within the system which is so hard on them. However, this sale system was implemented as an open critique of the art market. To decommodify artworks and acknowledge that art is also very valuable to people who can’t afford it – this was its goal.

People who wanted to purchase the artwork had to write their suggestions in the book. And some people were sitting in front of it for quite a while thinking: what can I offer? What is my skill, what is of value that I’m doing?

What do you like about this practice?

I like how it creates accessibility to become an owner of artwork without having to touch money. What you need is time or a certain skill in a specific craft. People who wanted to purchase the artwork had to write their suggestions in the book. And some people were sitting in front of it for quite a while thinking: what can I offer? What is my skill, what is of value that I’m doing? And I think this was a beautiful moment because in the end, everyone found something. I also want to continue this idea, even though for the Shells of the self show I had a price list.

Right, since December you got yourself the place at Chmielna 10A and curated the first show in the new location– Shells of the self. Can you tell me about it?

It’s a personal show which talks about domesticity. I wanted to create a narrative about “the house” or “the apartment” as a space itself, but also to refer to it as an emotional container: a container of intimacy and a private life. Shells of the self is about those walls that separate the private and the public, the inside and outside. Especially that my new place in Chmielna is kind of both: it is a public space, where people come, look at everything, and go. But at the same time it should also be my home; go beyond what an exhibition space or a gallery is. For the first show, I wanted it to be personal, since the personal is also political.

Strefa komfortu. Rozkwit i upadek nowego malarstwa 2013—2023

Piotr Policht

Piotr Policht

In English, you have a division between those two words: a home and a house. In Polish, it’s just one word: dom. How is it in your mother tongue?

In German we have even more words: das Haus, das Zuhause, and die Heimat. The first two can be the equivalents of a house and a home, but die Heimat is understood more in a national, cultural context. That’s where you feel at home in a broader sense, it is the outer “shell” that I am talking about in the show. A good example of die Heimat is an entire country, a city, or a specific scene. It is unfortunately appropriated by the nationalist vocabulary though.

For the first show at Chmielna, I wanted it to be personal, since the personal is also political.

What was the key to creating this story?

I invited artists who contributed to the fact that I’m here now (in Warsaw) and made me stay.

Can you tell me about the artists you invited and the pieces you chose?

Among the pieces that opened the exhibition space was an anonymous backglass painting in a wooden frame. It was a piece that I found in this apartment just after I moved in, behind a tile stove. There is no signature or name or anything mentioned on it, only a writing which says: “My army memories”, dated 1955. As this piece was in my place before me, I think it was very important to bring it to the very front. The second room was opened by two pieces by Cyril Tyrone Hübscher: Apartamento II and III. Apart from the fact that Cyril in his practice is often focused on architecture, he is the one who brought me to Warsaw and started my network.

Among the people I have to mention is Arman Galastyn. His most recent series of paintings goes back to growing up in Poland as a child from an Armenian family. He speaks about his experience of being othered and viewed as not belonging to Polish society. The eye, which is a very prominent symbol in his practice, stands for the scrutinization he was exposed to as “Other” – the Self-portrait on the Armenian rug is a great example of this notion. In the show, you could find another self-portrait by Arman, where his face and head were completely covered in hair. It is the artist’s idea of how people must look at him. Of course very exaggerated, which makes it funny, but bitter at the same time. The way Arman treats the topic of home in his work takes us back to the German word die Heimat.

I was especially captivated by the piece which shows a picture of a blue lamb. Can you tell me about it?

It is a piece by Deividas Vytautas, a Lithuanian artist, who was a support performer for Gloria Victoria Regotz during the very first Crash Club. he has left us but shafts of light sometimes grace the corner of our rooms is a cold, blurry, and very zoomed-in image of a white lamb. Within the blurriness, you see a raster, which exposes the fact it’s a photograph taken from a screen. Deividas is working with a vast image and video archive that he built up over a long time, while he was trained as a filmmaker. From this image archive, he started a series that moves in between tenderness and violence, the forbidden and the desired. His source sometimes comes from gay porn movies. The lamb has its symbolism of innocence and purity, but it talks exactly about this tension between the tender or the soft with the kinky or forbidden. It is also talking about this division between the private and the public.

I personally like performance, just because it goes against market rules. That is one of the reasons why I incorporate it into the Crash Club’s program.

Tell more about the performance program – maybe starting with the first Crash Club?

During the vernissage and the beginning of the second day at the Pavilion Bliska, it was fairly quiet. We were a bit worried that people would not show up. But closer to the performance more and more people came, and all of a sudden this very big space was very full. We were surprised but mostly just very thankful, and for me, it was a moment of validation. I realized: okay, the entire project was seen and it was really worth it.

It was a performance PLAY by Gloria Viktoria Regotz, which was done with a group of performers: Deividas Vytautas, Paulina Pawłowska, Dawid Dzwonkowski, Emma Szumlas, Kuba Stępień and Mattia Spich. It was about a bunch of, let’s say, bored or lost teenagers. They were staring into the void, taking flashy pictures of the audience, and killing time by playing games and fighting with each other. The scenography was very simple: a set of chairs and a table, on which there was a big, wooden cross. During the performance, the group painted the entire scenography with chalk, went outside and burned a wooden heart. To kill the fire they used a fire extinguisher leaving the entire audience in a white cloud of this extinguishing powder or whatever is in there. I think they created very beautiful moments and images and gave the audience much time to get lost in it, too.

I didn’t know that so many people would be interested in a performance within the frame of a gallery weekend, which is a commercial event, performing could have been disregarded, because it’s not really sellable. I personally like this medium, just because it goes against market rules. That is one of the reasons why I incorporate it into the Crash Club’s program.

Gloria performed one more time, during the Shells of the self show, she is as well among the artists contributing pieces.

Yes, this time Gloria was performing by herself, in the middle of the ongoing opening. At some point in the evening, she showed up with her laptop and started doing exercises against back pain. Her performances sometimes include unchanged quotations to activities she does in her own daily life. Gloria suffers from chronic back pain and she has to do these exercises at least one time of day – on that day she just came and did them on the exhibition floor. The performance is called Healing and is also a very personal piece about the body being “inhabitable” if one is not following the rules and the guidance of this trainer on YouTube.

Since I’m very interested in creating specific environments, I think performance is a substantial medium that should be part of a Crash Club. It is a way to build a mood that enables us to understand the narrative differently. During openings we often fall for the routine: everyone arrives with their moods and their days and then they part. That is really what I love about performance: to create this common mood of taking the time, looking at something, and being silent.

What is planned for the future?

I think a lot about the future, fantasizing, speculating, even manifesting new values, better politics, less harm from the systems we live under. But zooming in on my own path, there is the Swiss premiere of Liberty, Love and Loneliness II coming up, along with a series of new sculptures to sit on. (Manifesting a Polish premiere soon).

And at Crash Club, we will continue to create a context of intersections and encounters and engage with opposites to strengthen a sense of community. In a world that seems divided, encounter and collaboration are essential to move forward into a livable future. That is why I can’t wait for the big Crash Club during the next WGW because we want to do just that.